In my last few blogs, I have included sections of our recently launched book Connection: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe that described various elements of the colonisation process in Western Australia. Description of the colonisation process, which impacted so badly on Aboriginal people, provides a context to the story of the Carrolup child artists.

While carrying out research at the Battle Library, my good friend Mike Liu and I found a written description of life at Carrolup Native Settlement written by Revel Cooper, one of the best known of the Carrolup artists. He described life at Carrolup between 1940-46, before the arrival of teachers Olive Elliot and later Noel White. Conditions in the native settlement were appalling.

Mike and I later came across other information about Revel’s early life which I describe at the beginning of the section below. There was little doubt that Revel would have been traumatised by his experiences described here, and this trauma would have impacted on his social and emotional wellbeing, both as a child and an adult.

‘One of the young children at Carrolup in the early 1940s is Revel Cooper. Revel was born in 1934 in Katanning to Rita Hill and James Cooper. When he is five years old, Revel’s mother dies of heart failure during anaesthesia for an operation to remove an eye, aged only 27 years [1].

James Cooper asks Rita’s parents, Joseph Hill and Julia Mourish, to look after Revel and his four siblings. Four of the Cooper children are then made Wards of State, and they and their grandparents are taken from Katanning Reserve to Carrolup in May 1940.

Soon after, Revel’s youngest brother Carl, not yet one year old, becomes ill and is taken to Katanning Hospital. He dies ‘from enteritis’ a week later. On the same day, Revel’s other brothers, Jimmy (aged four) and Keith (two years old), are taken to Katanning Hospital suffering from enteritis. They are returned to Carrolup two and a half weeks later. In the doctor’s opinion, they will never be strong.

Revel’s grandfather Joseph Hill dies at Carrolup in May 1942.

Most of the Aboriginal children living at Carrolup Native Settlement have been taken from their parents, some of whom live on the north side of the river from the compound. They are not allowed free access to their children [2].

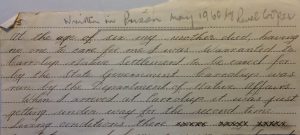

First page of Revel Cooper’s letter about Carrolup, written in 1960. Doreen Trainor Collection, J. S. Battye Library of West Australian History.

In his later refections on life at Carrolup, Revel Cooper describes the living conditions in the settlement as being of ‘the very lowest standards’.

‘The elder natives were issued with clothing which I recall consisted of dungarry pants army Boots woollen flannels and a very tough shirt made from a cheap government material from this same material two pieces of clothing were made for women this being their complete dress.’ [I have not altered Revel’s original words in this communication, or used {sic}, for purposes of clarity.]

The two dormitories where the children live are stone buildings, each consisting of two rooms and a bathroom.

‘We were locked in our respective dormitorys at 5pm winter and summer, with no drinking water a open sanitary buckett was placed in the centre of the floor, being afraid of the supernatural we were afraid to leave our beds at nights as a result of this the sanitary buckett was rarely used and the stench of urine soaked rugs and matteras was something that only the ones that lived in them could bare to smell.’

According to Revel, the Aboriginal children of Carrolup run wild at this time—fighting, bad language and open lovemaking are commonplace.

‘Fights were numerous among women men boys and girls there was hardly a day passed without someone fighting. Bad language wasn’t considered as such, among us and was used as normal words in our everyday speech. There was open love making at every corner under every tree. At the time we saw no reason why we boys and girls should practis what we saw. The results of what we got up to at every oppertunity would shock any normal present day family…’

… One supposedly kind Superintendent to keep us out of mischief supplied us with Rubber and catapults to our hearts desire. After slaughtering birds and other species of wildlife (including domestic cats) the novelty wore off. Then we turned our attentions to glass windows after which we turned on one another.’

Bullies prey on some of the children, who do not report them for fear of the consequences.

‘We had our bullies among the older boys as well. In the winter they visited our beds if we had three rugs we parted with to or else. If we had one they took that for spite. We dare not report these culprits because we knew the results, no matter what we did against them we always payed.’

Revel attended school ‘on and off’ for as long as he could remember. ‘In the latter part of the war we had no schooling at all.’ CONNECTION: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe. David Clark, in association with John Stanton. Copyright © 2020 by David Clark

[1] The information about Revel Cooper and his family described in the first four paragraphs of this chapter were obtained from a Department of Native Affairs file on Revel’s father, James Cooper, and from an ancestry report on Revel Cooper provided by the late Jan James. You can learn more from my blog Revel Cooper’s Early Life.

[2] Records show that Revel Cooper (aged 7 years) and his sister Maudie [sometimes spelt Maud or Maude] (9 years) attended school at the beginning of the school year in 1941. Others who were at school at that time and play a significant role in our story include Reynold Hart (6), Milton Jackson (7), Claude Kelly (8), Barry Loo (7), Morton Miller (9), Dulcie Penny (8) and Vera Wallam (7). Department of Native Affairs 598/41, State Records Office of WA. (Please note that the ages stated above are not exact, as birth dates of Aboriginal children were rarely known at this time. The white authorities assigned children a birth date, often the 1st January or 1st July, as if they were racehorses.)

The Carrolup School Journal reveals that Mervyn Smith started school on the 9th February 1945 and Parnell Dempster on the 10th of July 1945.