This is the third of a series of blogs that considers the social, political and cultural context existing prior to our story of the Aboriginal child artists of Carrolup. I focus on the policy of removing Aboriginal people from their families, which resulted in what we now know as The Stolen Generations. Sections are taken from our forthcoming book.

Mr Auber Octavius Neville was Chief Protector of Aborigines between 1915 and 1940, initially working under the Department of Aborigines and Fisheries. He was a bureaucrat of great determination who devoted his talents and energies to tackling what he perceived as an emerging racial problem in Australia. He did not just exert a profound influence on policy and practice on Aboriginal affairs in Western Australia, but also influenced related policy across the country.

Today, ‘Neville the Devil’ is remembered by Aboriginal people more than any other white person as being responsible for the tyrannical control that was exerted over Aboriginal people.

Neville’s appointment as Chief Protector resulted in a period of strict implementation of the 1905 Aborigines Act and unprecedented interference in the lives of Aboriginal people, particularly in the South West of Western Australia.

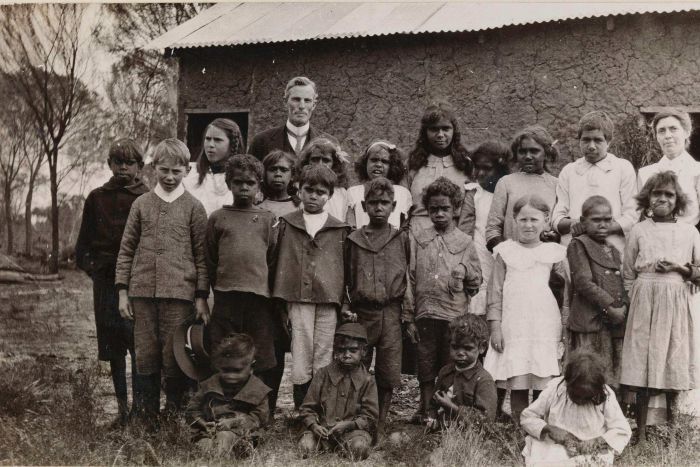

In the early years of his position (1915 – 1920), Neville focused on the development of the government-run ‘native settlements’ at Carrolup and Moore River. The idea of these settlements was to isolate Aboriginal children from their parents, then educate and train them for unskilled occupations, e.g. domestic service and farm work. These settlements would not only serve the purpose of giving Aboriginal children the ‘opportunity’ to shed their Aboriginal background, but would also appease white communities who did not want Aboriginal people camped on the edges of towns.

Another important aim was for these settlements to be developed with the minimum amount of government expenditure, which is what happened. The settlements became places that had shocking living conditions, harsh controls and cruel punishments.

During his time as Chief Protector, Neville became increasingly concerned about Aboriginal people of mixed descent, particularly those in the South West. He felt that ‘full-bloods’ should be left alone and no attempts made to civilise them, although provision should be made for their physical comfort. He believed that they would die out in due course, despite having no evidence for this view. His views were stated clearly to delegates from around the country in the Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities in 1937.

In my opinion, however, the problem is one which will eventually solve itself. There are a great many full-blooded aborigines in Western Australia living their own natural lives. They are not, for the most part, getting enough food, and they are, in fact, being decimated by their own tribal practices. In my opinion, no matter what we do, they will die out.’ Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities, Canberra, 1937, p. 16

Neville was convinced that ‘half-castes’ could make as good a citizen as anyone else. However, he saw the need for the increasing population of ‘half-castes’ to be assimilated into the white community. They needed to be taken control of at a very young age. As he pointed out at the Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities:

If the coloured people of this country are to be absorbed into the general community they must be thoroughly fit and educated at least to the extent of the three R’s. If they can read, write and count, and know what wages they should get, and how to enter into an agreement with an employer, that is all that should be necessary. Once that is accomplished there is no reason in the world why these coloured people should not be absorbed into the community. To achieve this end, however, we must have charge of the children at the age of six years: it is useless to wait until they are twelve or thirteen years of age. In Western Australia we have the power to act to take any child from its mother at any stage of its life, no matter whether the mother be legally married or not. It is, however, our intention to establish sufficient settlements to undertake the training and education of these children so that they become absorbed into the general community.’ (p. 11)

Neville stoked the fire of fear at this conference, and made clear his view of the future for Aboriginal people in Australia.

‘Are we going to have a population of 1,000,000 blacks in the Commonwealth, or are we going to merge them into our white community and eventually forget that there ever were any aborigines in Australia?… I see no objection to the ultimate absorption into our own race the whole of the existing Australian native race.’ Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities, 1937, p. 11

Neville revealed a heartless nature, which was common amongst the white population of Australia, in various ways:

I know of 200 or 300 girls, however, in Western Australia who have gone into domestic service and the majority are doing very well. Our policy is to send them out into the white community, and if a girl comes back pregnant our rule is to keep her for two years. The child is then taken away from the mother and sometimes never sees her again. Thus these children grow up as whites, knowing nothing of their own environment. At the expiration of the period of two years the mother goes back into service so it really does not matter if she has half a dozen children.’ (p. 12)

Some Aboriginal girls were raped by white people when in service, returned to a government settlement to give birth, and then had the child taken away. They would then be sent back into service.

Neville introduced and maintained his policies against Aboriginal people despite knowing that they hated being institutionalised, and that they had a tremendous affection for their children.

Reference has been made to institutionalism as applied to the aborigines. It is well known that coloured races all over the world detest institutionalism. They have a tremendous affection for their children. In Western Australia, we have only a few institutions for the reception of half-caste illegitimate children, but there are hundreds living in camps close to the country towns under revolting conditions. It is infinitely better to take a child from its mother, and put it in an institution, where it will be looked after, than to allow it to be brought up subject to the influence of such camps. We allow the mothers to go to the institutions also, though they are separated from the children. The mothers are camped some distance away, while the children live in dormitories. The parents may go out to work, and return to see that their children are well and properly looked after. We generally find that, after a few months, they are quite content to leave their children there.’ Initial Conference of Commonwealth and State Aboriginal Authorities, 1937, p. 17

The picture that Neville painted about what was happening to Aboriginal people in Western Australia was often different to the reality. There was no evidence for the last line of the above statement. Aboriginal mothers were devastated by the loss of their children, and many spent the rest of their lives trying to find them.

Of course, Mr Neville was not solely responsible for these policies. He was acting in accord with government policies, which were strongly supported by many white people. In fact, an increasing prejudice towards Aboriginal people from the first decade of the 20th century, particularly in the South West, had resulted in calls for them to be excluded from contact with white society.