In the first weekend of November 1948, Frank and Myrtle Amos, members of the Native Rights and Welfare League, visited Carrolup as the guests of the Whites. They had previously hosted at their home two of the Carrolup boys who were involved in the Boans exhibition. After their visit, Mr and Mrs Amos decided that they would like to help the children of Carrolup by organising a holiday camp for them.

The Department of Native Affairs granted approval for the holiday camp idea, and two senior members of the military gave permission for the children and adults to use Swanbourne Military camp, which is next to a beautiful sandy beach, for eleven days from the 15th of January. Full facilities were put at the disposal of the organisers of the camp.

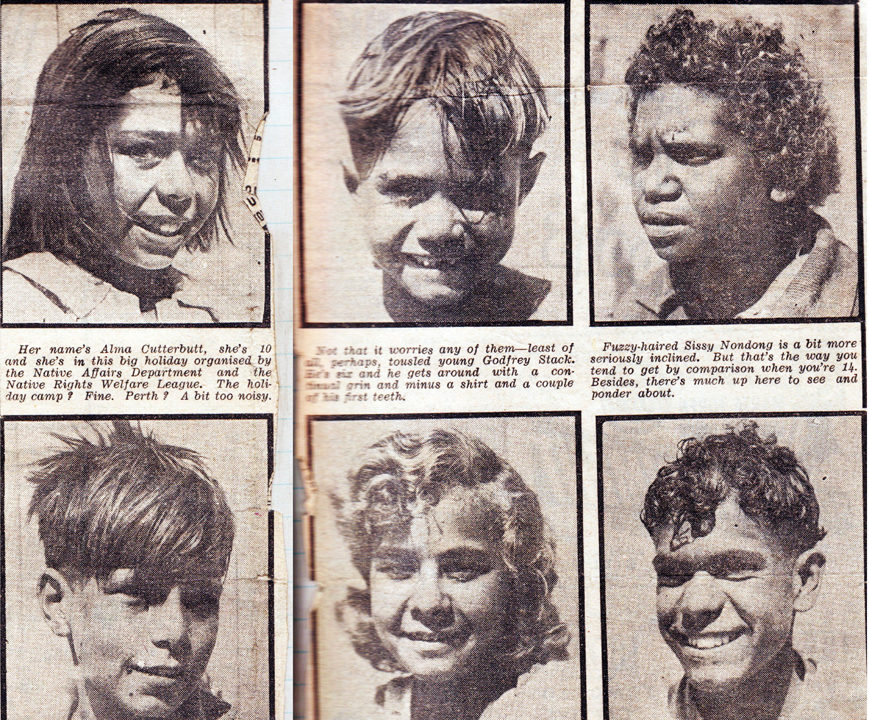

A number of activities were planned for the children, including visits to Perth Zoo, Kings Park and a museum, a trip down the river to Fremantle, an afternoon of instruction from the Swanbourne Surf Life-saving Club, and a film night at an open-air theatre. Although some of the children had previously been to Albany, many had never seen the sea. Only four children, those boys involved in the Boans exhibition, had previously visited the city of Perth. [Click on the image above to see names of the six Carrolup children photographed by The Daily News at Swanbourne.]

Here is a section from our forthcoming Carrolup book which relates to this holiday camp:

“In the Report that he writes for the Department of Native Affairs (and others) after the camp, Mr Amos talks very favourably about the Carrolup children [1].

‘We found the children well-mannered and obedient, the older ones realising that a great deal depended on their behaviour. They reciprocated our trust and showed their appreciation of it in many ways.’ Frank Amos, Holiday Camp Report, p. 3 (as written at top of page)

‘Great pride was taken in the cleanliness and appearance of the dormitories which were inspected every morning.’ (p. 4)

COMPANIONS: At the Swanbourne camp for native children Mildred Jones and Joan Indich take a small white friend, Jane Heller, for a swim. The West Australian, 19th January 1949.

The children are given considerable freedom, the camp rules being of a positive nature, rather than a series of prohibitions. For example, the dormitories are not locked, and the children can turn on lights at night. These privileges are not abused. The children make use of the shower baths and toothbrushes supplied, and the older girls wash and iron their own clothes.

However, Mr Amos reports that there was evidence of previous mass neglect in the care of the younger children during their time at Carrolup:

‘… their heads were verminous and a mass of nits, and several were suffering from a skin affection which appeared to be akin to scabies. Mrs [redacted] attempted to cope with the condition of the heads, but it was impossible to complete such a task in twelve days.’ (p. 4)

There are also problems for the older children:

‘The cut and fit of the children’s clothes did nothing to inspire confidence or self-respect, especially when they were out on trips and in contact with the white population. The older boys were very conscious of their ill-fitting and badly-made clothes. Miss [redacted] obtained frocks from her friends for some of the older girls. The preparation of the children’s clothes for their outings entailed a great deal of extra work for the ladies and they are deserving of the highest commendation for their efforts. The attitude that anything is good enough for the native child is utterly wrong in principle and militates against any attempt to develop a feeling of confidence and self-respect in him. On any future occasion it would be essential for each child to have two sets of street clothes and furthermore, that the clothing should be packed in suit cases not a couple of sacks.’ (p. 4)

It should be noted that the children’s clothes were not being made by Mrs White at this time, as she was too busy with her teaching duties. In relation to the four senior girls from Carrolup, they were:

‘… of great assistance to us. We worked together in complete harmony and they carried out their respective duties cheerfully and to the best of their ability. Their work was so arranged that they were enabled to enjoy the holiday with the children. Their understanding of the individual children did much to assist us in dealing with the little problems and disputes which inevitably arise amongst any group of children.

We trust that our contact with us and our way of living will be of value to them in the future. We, in turn, will remember our happy association with them…’ (p. 4)

Mr Amos finishes his report in a positive manner, saying that the Holiday Camp:

‘… was a great experience and experiment and we have learnt much from our close contact with the Carrolup children. Through taking the children out amongst white people, we discovered too, that there are numbers of people who are well disposed, sympathetic and willing to do whatever they can to improve the lot of native children. This desirable attitude in the public is most encouraging and only needs direction to be put to practical use.

We wish to pay a tribute to the great work which Mr. and Mrs. Noel White have done and are still doing for the social betterment of these children and trust that their altruism and high endeavours will not be in vain, but will be utilised to the full in implementing the new, progressive and enlightened policy which you, Mr. Commissioner, are inaugurating and which offers hope for a happier, more purposive and objective for the rising and future generations of our native population. We offer you our services to assist you in your great work.’ (pp. 4 – 5)”

CONNECTION: Aboriginal Child Artists Captivate Europe. David Clark, in association with John Stanton. Copyright © 2020 by David Clark

[1] Letter from Frank Amos to S G Middleton, 26th February 1949. State Records Office of Western Australia.